Dear friends,

At the end of the first episode of the Ask a Buddhist Ethicist podcast, I realized I had spent a good 20 mins yapping about the precepts, and completely missed any discussion on karma.

Karma is the mechanism by which Buddhist ethics function and so before we dive into the more themed discussions we have planned for this year (AI, lying, sex, community… you know, light stuff), I want to make sure we’re working from a shared foundation.

Karma is a term that's been misunderstood, largely because of its over-simplification in popular culture. This episode will hopefully clear up some of the misconceptions, especially those that are harmful to oppressed groups.

I considered making this podcast a bit fancier, with music and uploading it to Spotify. But I realized that I prefer sending you the audio directly—like a personal voice note from me to you.

Please enjoy the second episode, and if you prefer reading, I’ve included a AI-generated transcript below.

I’d love to hear your thoughts—your reflections, questions, or anything that resonates. You can share with me by responding to this email or by commenting on this post.

With love,

Adriana

P.S. I’ve also included some reminders and updates below—just keep scrolling.

Listen to Episode 2 of the Ask a Buddhist Ethicist podcast:

In this episode, I dive into:

The nature and historical context of karma in Buddhist teachings

Karma's cosmological role and impact across the six realms

How intentions shape karma's effects

Karma's psychological operation through dependent origination, exemplified by the 12 links of cause and effect

The misconception of karma as punishment and its harm to oppressed groups

The connection between karma, no-self, and the social responsibility for collective karma

A few reminders and updates:

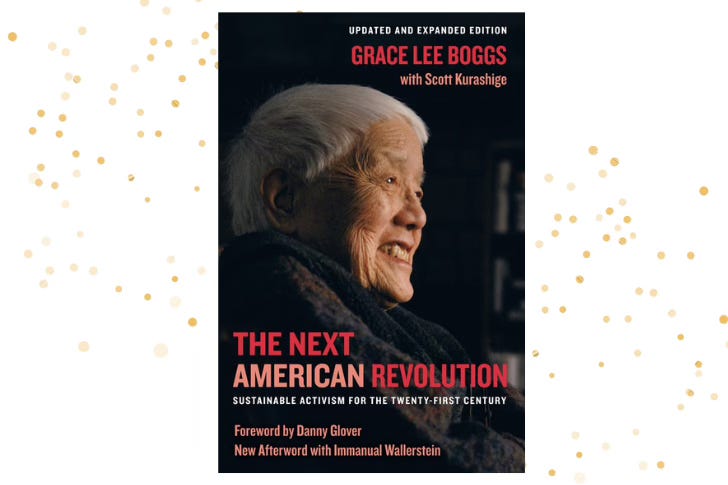

Join March’s Engaged Dharma Book Club! We’re reading Grace Lee Boggs’ The Next American Revolution and are kicking off with weekly Chats via the Substack App this upcoming Monday, March 11th. The live Zoom discussion is Sunday, March 30th 3-5pm ET. If you’d like to join, you can upgrade now and join in on all the monthly workshops, book clubs, and (soon to start) weekly meditation.

A huge THANK YOU to everyone who has donated to my interfaith Palestine mutual-aid fundraiser. After my last email was sent out, a few of you kind, generous souls helped me surpass my goal for the week. We’ve fundraised $900 out of the $2000 commitment I made for April 9th. Can you help me get to $1250 by the end of this week? That means we need another $350. You can Venmo me @adriana-difazio or you can give to the orgs directly linked here and put down my initials (AD) so it can be counted towards my goal.

I had the pleasure of being on

’ podcast A Soulful Revolution. I talk maybe a little too frankly about motherhood and engaged spirituality. It’s the type of activist-mom-spirituality conversation I wish I could’ve listened to when Bo was still tiny and I couldn’t go to any protests and would regularly go multiple days in a row without showering. It’s great!FYI: I accidentally deleted the replay post for the “Introduction to Socially Engaged Buddhism Workshop” on the backend 😂 It’s been reposted but your last email will likely redirect you to “this content is no longer available.”

AI transcript:

Hello, welcome everyone to episode two of Ask a Buddhist Ethicist, a podcast where we dive into big thorny ethical questions regarding community, culture and social change and wrestle with them from a Buddhist perspective. My name is Adriana DiFazio and I'm our host. I'm a Buddhist meditation teacher, practitioner-scholar, chaplain, facilitator, and parent. And I'm so excited to be recording the second episode of this new project in which we have the opportunity to wrestle with Buddhist ethics, the precepts out loud.

In our first episode, I gave us an overview of Buddhist ethics through the teachings on the precepts. And then within the last 20 seconds or so of the episode, I realized I hadn't really spoken about karma whatsoever. And karma is really the mechanism in which Buddhist ethics function. And so I thought before we dive into more of the thematic questions for the rest of this year. It would probably be smart for us to start from a shared common foundation with an understanding of what karma really is.

So karma is perhaps one of the most misunderstood Buddhist teachings. And I think this is primarily due to the fact that the term is thrown around in our popular culture quite often. I mean, the number one reference that I think of is Taylor Swift's most recent song where she's like, karma is your boyfriend, that one. But karma is a Sanskrit word, literally meaning action or doing. In Buddhist circles, you'll sometimes hear this in reference to the Pali term kama, K-A-M-M-A.

And what's important to know is that karma was a teaching that was pre-existing within the Brahmanical Vedic culture in which the Buddha came to be. And karma at the time had its very, very specific defined understanding. Karma was in reference to ritual sacrifice that was done in the Brahmanical tradition and it was directly in reference to either ritual sacrifices that has a specific amount of efficiency that would allow for a preferable rebirth in the next lifetime.

And so when the Buddha started practicing, there was a shift in how he translated karma. And so he referred to karma as any type of action, whether that be mental, verbal, or physical. It's important for us to recognize karma here does not necessarily mean only outward-facing action that can be perceived by other people, but can also be actions of our thoughts, our mental workings. And that's karma too, even though it is not outwardly visible to other people.

With that being said, it's considered that the Buddha taught karma within a cosmological worldview at the time as a skillful means for the pre-existing culture and understanding of karma within an understanding of rebirth in one's next life. And so karma, even though there was a slight transition in what it was in reference to, it was no longer necessarily only an attribution to ritual sacrifice, but to be action at large, mental, verbal, or physical, it was still within this moral feedback loop that meant individual behavior led to either a higher or lower rebirth into one of the six realms.

So the six realms in Buddhist cosmology refers to one of the possible realms that you could be reborn into. So in Judeo-Christian cosmology, we really just view this in terms of, you know, Earth, Heaven and Hell. But in Buddhism, there are six different ones. And so we currently inhabit the human realm. But below us, there's also the animal realm, the hungry ghost realm, and then the hell realm. And then above us is the jealous god realm, and then like the heavenly, heavenly god realm. That's definitely not the technical term, but you could probably just deduce what that means.

But interestingly, the human realm is actually the best realm to be born into, because it offers the perfect balance of pleasure and suffering that allows us to feel motivated enough to actually seek moksha, extinction or liberation from the path of rebirth of samsara within these six realms of existence. And so the Buddha taught the Eightfold Noble Path as a means of training to exit the cycle and ultimately lead to the cessation of suffering. And so the goal in Buddhism is actually to not be in any of these realms whatsoever and to extinguish one's own karma. And so this cosmological function or understanding of karma within the six realms, some Buddhists believe that that's actually the case in terms of being reborn for themselves.

While a more modernistic understanding of the six realms could be viewed on a psychological level in the sense that we can inhabit one of the realms throughout within 10 minutes, within a day, within a week, within a period of our life, we can move through one of the realms quite quickly. So for instance, each realm has a different characteristics. The hungry ghost realm, for example, ee are insatiable. It's characterized by this incessant craving in which we are never satisfied. Traditional illustrations of the hungry ghosts in this realm, they have really skinny throats and then these big, loaded bellies to represent their suffering. And then the god realms, like the jealous god realms, I think the best example of a jealous god realm is the feelings that you get, perhaps, when you're scrolling through some type of social media and rather than feeling a sense of sympathetic joy for someone else when they experience something positive, we have that crunchy, clingy feeling where we don't... Our impulse isn't one to necessarily automatically feel happy for them. I think that feeling in itself is us being in the jealous god realm.

This cosmological perspective alone can be somewhat unhelpful because what can happen is folks can try to accumulate wholesome karma out of fear of being reborn into a lower realm. And what's important to recognize is that karma is driven by our intention. So we have actions and then there's an intention that is underneath the actions of body, speech, and mind.

And so in Buddhism, the intention is what’s important and there's unwholesome or wholesome intentions that drive our karma. Wholesome intentions are ones that promote generosity, compassion, or understanding. And then unwholesome intentions are based in one of the three poisons or kleshas, which are greed, aggression, or delusion. And so it doesn't matter necessarily if we act virtuously, if our intention behind those virtuous actions are unwholesome, if they're based in fear, if they're based in aggression or clinging, the karmic seeds of those actions are still unwholesome. And so that’s really important for us to recognize when we consider our own actions and our own karma.

We really have to offer ourselves a contemplation of what are our intentions, what are we motivated by. And it really demands us to look at ourselves clearly beyond the surface. I think what's really helpful is that the three poisons give us a framework to interrogate our motivations and look at ourselves honestly. And then it also gives us an opportunity to place a lot more, for lack of a better term, intention on our actions.

So it just offers a different value or weight to everything that we do. Not in a neurotic sense in which we become scared to do anything, but that we recognize that there is value. We become a lot more discerning about how we go about and move through the world.

An example of this for me of just reflecting in which throughout my life I may have had outwardly facing wholesome behavior, but my intention was based in fear or craving. I think a lot about my conditioning for overachievement as a young adult in regards to academics and being perceived as good and being a people pleaser. And if I really interrogate and look closely as to what really were my motivations for that, it was based in a sense of craving and being perceived in a certain way.

In many ways, it's like once we're able to really reckon with what our intentions are behind our actions, we can set ourselves free, which is the whole point of our practice. And so with that being said, on a more psychological level, karma also operates within what is known as the 12 links of dependent origination. So dependent origination is its own Buddhist teaching and is based on circumstances arise based on a series of causes and conditions. More simply, dependent origination is a teaching based in interdependence, that we are all connected in some way, and that nothing exists in isolation.

Dependent origination is often represented as a wheel, and there's these 12 lengths of cause and effect. It always starts with a fundamental misunderstanding, misperception, or ignorance. I like to think about this as just a lack of awareness. We don't know. And therefore, we keep feeding our karmic wheel along these 12 links. And I like the imagery of the wheel because it helps us remember that karma has a volitional energy. Our karma is not just isolated actions of body, speech, and mind. But they feed and build upon one another.

There's a habit energy. In the same way that you would be riding a bike and you don't necessarily need to keep on pedaling on the bike for those wheels to keep on turning, our karma functions in a very similar way. The 12 links of dependent origination really describe our moment to moment experience in the sense of how we create karma in real time.

So for instance, this can describe any type of action that we're taking. Something as simple as picking up your phone, something as simple as opening an email, having a conversation with someone. And when we encounter this experience, we have some type of feeling tone that happens. We either like it, we don't like it, or maybe we feel neutral about it. And then we choose whether we're conscious of this decision or not to react in some type of way. And so that is our karma. That is the action of body speech or mind that we have taken.

Oftentimes, most of the times, we are unaware, completely unaware of our choice here. And just to illustrate this, I want to share from Dr. Larry Ward's book, America's Racial Karma. He says, studies by neurobiologists and psychologists researching habit formation indicate that 40 to 95 percent of human behavior—how we think, how we respond with emotions, what we say, and how we act—falls into the habit category. So when it comes to deeply rooted thoughts and behaviors, however good we think our intentions may be, without insight about the need to change, the strong resolve to make it happen, a good 50% of the time we will default to habit.

Isn't that wild and also terrifying at the same time? Yeah, I mean, Dr. Larry Ward says it very well. This strong resolve, this awareness of our choice, ultimately matters. And so when people mention that mindfulness meditation allows us to grow the gap between our felt response and our action, this is what they're referring to. This is why meditation practice is so important. We need a formal embodied practice to slow down our karmic and volitional energy. And then when we are actually practicing and we have a consistent practice, we can more easily see our karma playing out.

We can more easily see or find ourselves within that gap between whatever our experience and our response. We can reclaim our sense of agency and our discernment in those moments. And so having an understanding of karma from a personal practice-based perspective, we can more intentionally choose to plant wholesome or unwholesome seeds in terms of our day-to-day behavior.

And it's also incredibly helpful in terms of just our seated meditation practice, because then with the simple instruction of noticing that you're thinking and then bringing yourself back to your breath, we have to having this larger view of like, okay, what seeds do I want to plant here? Do I want to continue ruminating on X, Y, and Z? Or do I want to bring myself back and cultivate my concentration? Or do I want to contemplate on loving kindness and generosity and patience? And so we're empowered by our knowledge, empowered by these teachings, to choose more wisely.

So now that we have an individual and cosmological understanding of karma, I wanna clarify the common misperception of karma as a system of rewards and punishment as it can be really dangerous to oppressed and marginalized groups of people. We have to remember that karma is not linear, it is not prescriptive, and it is not direct, always.

Some types of karma we can see very clearly. We can push something off our table and everything can go spilling, shattering onto the floor. That is karma. And when we consider the karma of individuals, the karma of collective groups of people, our social and collective karma, it is rarely that simple, if ever. And that's why it's so important for us to remember that karma functions with dependent origination. There are many causes and conditions that have come together for certain realities and circumstances to arise.

When we see groups of people suffering disproportionately, it's unhelpful to ascribe a certain sense of punitive, retributive justice and blame on individuals that are suffering. It's first and foremost, uncompassionate and unhelpful. And two, it's not based in reality. That type of karma that ripens on such a large social scale means that there were many, many, many, many seeds planted.

It doesn't necessarily mean that group of people planted a ton of unwholesome seeds personally. It could be unwholesome seeds from other people, from other groups of people, on a social scale. And so what's helpful in terms of understanding karma in partnership with this sense of dependent origination is that it depersonalizes everything.

It's connected to the Buddhist teaching of no-self. This idea that who we think we are, this solid sense of me is actually much less solid and permanent than we think we are. That we are actually not so separate or disconnected from other people, other beings, that we are actually much more permeable.

John Seed, the environmental activist, has this famous quote saying, I am part of the rainforest protecting itself. And that's a beautiful representation of this teaching of no self, that him advocating for the rainforest is not him advocating for something separate, but it's actually about protecting himself too, because he is part of the rainforest. We all are. Joanna Macy also has a book by the title of World as Self, Self as Lover. And that too is a representation of this Buddhist teaching of no-self, that we are all connected in some way.

When we take the teachings on karma, dependent origination and no-self together, we recognize that our karma is wrapped up in everyone else's. Our individual karma, the way that we choose to cultivate wholesome seeds for ourselves, not only directly impacts our own wellbeing and our own path to liberation, but actually informs and creates the conditions for other individuals’ path for liberation too.

What I love about karma is it allows us to make a deeper connection between the personal and the social or the personal and the political. It helps us take responsibility not only for ourselves but for other people. It helps us see the ways that we are connected and in solidarity with other individuals that are marginalized and oppressed. And it helps us break out of our own shell of self-centeredness, egocentricity that Buddhist meditation practice and spirituality can be inadvertently used to reinforce.

So in conclusion for this podcast episode, I think the key points that I want to make sure that everyone understands and that we are starting from as we begin to explore these more topical questions and themes together in the following episodes this year is that karma is not a simple moral system of rewards and punishment.

It's about understanding the deeper intention behind our actions and recognizing the complex web of conditions that shape our lives and the lives of others. And then as practitioners, consider our own moral actions of body, speech, and mind, and really reflecting on our intentions, examining our actions in the context of larger systemic oppression and harm.

And then to the best of our ability, avoiding using our karma to perpetuate that harm and hopefully planting wholesome seeds that help transform greed, aggression, delusion on a global scale. So that's all I have for episode two on karma. I hope this was helpful in terms of just offering us a foundation. If you'd like to explore karma more for yourself on a practice-based level, I recommend my mentorship program in which we really have an opportunity to look into the ways in which we can help deepen your own Buddhist meditation practice and reflection on the Eightfold Noble Path.

Some announcements, we have the Engage Dharma Book Club kicking off this upcoming Monday, March 11th with weekly chats via the Substack App. And then we have a live Zoom discussion on Sunday, March 30th, 3 to 5 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. And I'll be co-facilitating with my lovely friend, a fellow meditation teacher, community organizer, Jessica Angima. And then in April, we'll have our Engaged Buddhist Studies seminar. The topic will be The Transmission of Buddhism to the West. This is my expertise in terms of my graduate research, so I'm really excited to be able to share this with all of you.

And then last but not least, we'll be kicking off weekly meditation gatherings, either at the end of this month in March or the beginning of April. I'm still trying to figure out the logistics, but my hope and intention with sharing Buddhist meditation practice in a progressive, slow, non-consumeristic way is to really help everyone develop depth and a true connection, sense of agency to applying the nuances of technique for practice.

I feel like many of the meditation resources out there online kind of just feed us techniques without really recognition that all of these things are meant to be integrated very slowly and they take time and we may have all the techniques but they don't really matter if we aren't actually integrating, giving ourselves the time and container to embody them. So I'm hoping to be able to do that for us through these weekly meditation gatherings.

If you're interested in joining you can join the membership community through Radical Change. Just upgrade your subscription to a paid membership. And then I think that's it for now. So thank you again so much everyone and I look forward to our next episode. Take care.

Thank you for this clear and concise breakdown! While listening to the podcast, I thought a lot about the link between karma and personal + ancestral traumas (I also pulled out my copy of "No Bad Parts" because it brought to mind IFS and the concept of legacy burdens, those things we inherit from our parents and culture).

I appreciate the articulation of the propulsive energy of the wheel, that some of the more difficult aspects of ourselves arise not because they were "deserved" but because something has been set in motion before us. And the imagery of the bike coasting along without our pedaling > that we don't have to keep pedaling, and instead we can plant wholesome seeds to stop the propulsive energy of our trauma. 🌀